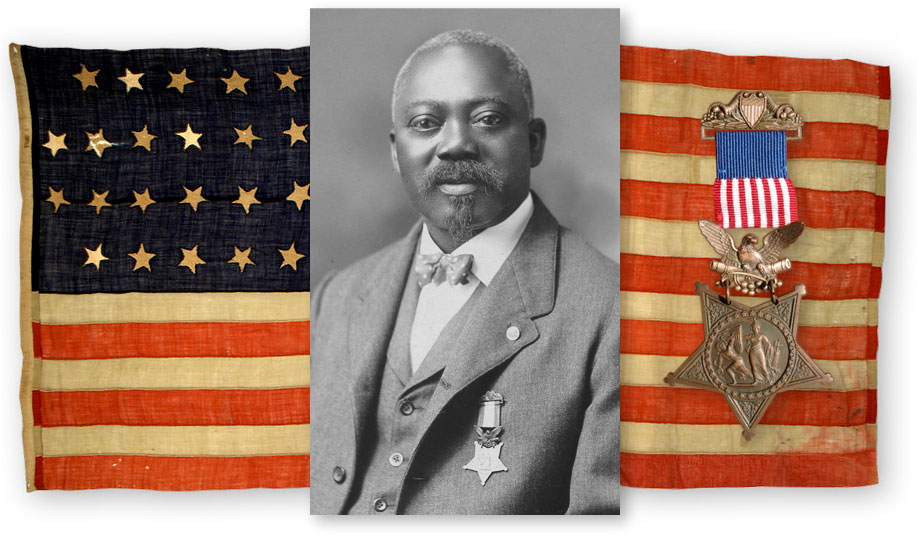

The First African American Medal of Honor Recipient

Sergeant William Carney

Fort Wagner, South Carolina

July 18, 1863

Perhaps you’ve seen the movie “Glory” — an epic based on the true exploits of black soldiers during the Civil War. One of the most gripping portions is the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. Just two weeks after General Grant’s victory at Vicksburg a large Union force gathered outside the walled Confederate fort on the beach at Fort Wagner, an obstacle considered essential to Grant’s plan to capture Charleston. From the bay six ironclad Union ships began the bombardment. Lying on the sandy beach within 1000 yards of the fort were members of the Union infantry including the 600 men of the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry. Behind them was the 6th Connecticut, but on this day it would be the black soldiers of the 54th who would lead the assault.

The Civil War was almost two years old when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. With that historic step, for the first time, black American’s were encouraged to enlist in the Union Army. Among the enlistees was a young man named William Carney. Born on February 29, 1840 at Norfolk, Virginia, William Carney’s mother was a slave to Major Carney. Prior to the Civil War there was no program for educating young black men in the South, but Carney was fortunate enough at the age of 14 to attend a secret school where he learned to read and write. Emancipated when Major Carney died, young William Carney had moved to Bedford, Massachusetts and began preparing for a future as a minister.

When volunteers were requested to man the Union Army in 1862, and following President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, William Carney temporarily set aside his plans to enter the ministry. He later stated, “I felt I could best serve my God by serving my Country and my oppressed bothers.” He became a member of, and trained with, the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry’s C Company. Most of the soldiers in the unit were conscientious and focused on the task at hand. Union General Ullman later said of the men in the all-black units, “They are far more earnest than we…They know the deep stake they have in the issue.”

The assault on Fort Wagner would be the first real test of these young black, Union soldiers–everyone of them a volunteer. Though the 54th Massachusetts was Federalized, it was an entirely separate regiment. Despite Lincoln’s Proclamation and widening acceptance of these “soldiers of color”, some prejudices and preconceived notions still prevailed…even in the North. So it was that the brave but un-battle-tested young men of the 54th found themselves lying in the sand, waiting for the order to lead the advance on Fort Wagner. Among those brave soldiers was 23-year old Sergeant William Carney.

As evening began to fall the order came. The brave young men jumped to their feet and charged at a run towards the enemy stronghold. The Confederate defenders were prepared for them and cannon fire and bullets flew through the air, devastating the advancing 54th. Heedless of the danger and often fighting hand to hand, the 54th continued the advance. Ahead of them Sergeant John Wall carried the colors, the red, white and blue of the United States of America. Suddenly a rifle bullet dropped Sergeant Wall and the flag began to fall to the ground. Sergeant William Carney threw his rifle aside and grasped the colors before they touched the ground.

As evening began to fall the order came. The brave young men jumped to their feet and charged at a run towards the enemy stronghold. The Confederate defenders were prepared for them and cannon fire and bullets flew through the air, devastating the advancing 54th. Heedless of the danger and often fighting hand to hand, the 54th continued the advance. Ahead of them Sergeant John Wall carried the colors, the red, white and blue of the United States of America. Suddenly a rifle bullet dropped Sergeant Wall and the flag began to fall to the ground. Sergeant William Carney threw his rifle aside and grasped the colors before they touched the ground.

Another rifle slug sliced through the air, this one hitting Sergeant Carney in the leg. With soldiers falling all around him Carney mustered the strength to ignore the pain in his leg, hoist the colors high in the air, and continue to lead the advance. Somehow he gained the entrance to the fort and proudly planted his flag…but he was alone…everyone else either killed or wounded. The solitary figure and his flag pressed against the wall of the fort for half an hour as the battle raged on. Then an attack to the right of the fort’s entrance drew the enemy’s attention away from him. He noticed a group of soldiers advancing towards him and, mistaking them for friendly troops, hoisted his flag high. Again gunfire split the air as Carney realized all too late that they were Confederate soldiers.

In that moment of danger Carney remembered the flag that represented all he held dear and was fighting to protect that day. Rather than dropping the flag and fleeing for his life, he wrapped the flag around the staff to protect it and ran down an embankment. Stumbling through a ditch, chest-deep in water, he held his flag high. Another bullet struck him in the chest, another in the right arm, then another in his right leg. Carney struggled on alone, determined not to let his flag fall to the enemy.

From the safety of the distance to which they had retreated, what remained of the valiant warriors of the 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry watched the brave Sergeant struggle towards safety. A retreating member of the 100th New York passed Carney and, seeing the severity of his wounds said, “Let me carry that flag for you.” With indomitable courage Sergeant Carney replied, “No one but a member of the 54th should carry the colors.” Despite the sounds of rifle and cannon fire that followed him, Carney struggled on. Another enemy bullet found its mark, grazing his head, but Carney wouldn’t quit.

Amid the cheers of his battered comrades Sergeant Carney finally reached safety. Before collapsing among them from his many wounds his only words were, “Boys, I only did my duty. The flag never touched the ground.”

Several months later Sergeant William Carney, propped up on a cane from the injuries to his right leg, posed for a picture holding the flag he had risked so much for that day at Fort Wagner. The following year he was discharged from the army for the disabilities of his wounds. William Carney never realized his dream of becoming a minister. Moving back to New Bedford he worked for several years as a mail carrier. After that he worked as a messenger in the Massachusetts State House.

It was not unusual for acts of valor accomplished during the Civil War to go unrecognized for many years. More than half of the 1520 Medals of Honor awarded for heroism during that period were not awarded until 20 or more years after the war. On May 23, 1900 Sergeant William Harvey Carney was awarded his Nation’s highest award, the Medal of Honor. Though by that time several other black Americans had already received the award for heroism during the Civil War and the Indian Campaigns, Sergeant Carney’s action at Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863 was the first to merit the award.

William Harvey Carney died at his home in New Bedford on December 9, 1908, and is buried in the Oak Grove Cemetery there. His final resting place bears a distinctive stone, one claimed by less than 3500 Americans. Engraved on the white marble is a gold image of the Medal of Honor, a tribute to a courageous soldier and the flag he loved so dearly.