Letter from Captain Robert R. Newell

Company B, 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

March 9, 1864

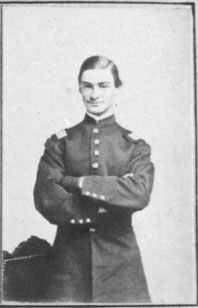

Captain Robert Ralsten Newell served in Company B. He was born 22 December 1843, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When he joined the army he was single and a student at Harvard. He was commissioned from civilian life as a 2nd Lieutenant on 12 December 1863, and joined the 54th on 5 January 1864. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant on 4 February 1864, but did not find out about his promotion until 26 March, so he fought in the Battle of Olustee as a 2nd Lieutenant.

In 1865, he led Company B into Charleston, South Carolina, one of the first sizable bodies of colored troops to enter the city. He was promoted to Captain on 11 July 1865, and was discharged on 20 August 1865, at Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. At the end of the war, he was serving on the staff of General E.N. Hallowell. Robert Newell died in Cambridge, Massachusetts on 23 February 1883.

The above information obtained from A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the 5th Massachusetts, 1863-1865 by Captain Luis R. Emilio.

This letter by Captain Newell was provided by his great nephew, John S. Moore of Concord, Massachusetts.

The letter is from Captain Newell to his brother William.

Rifle Pits near Jacksonville

March 9th 1864

Dear Will,

I have had so much to think of that my memory fails on some points, and I could hardly have told you certainly whether I had written more than one letter to you, though I had a strong impression I had written two or three, but I can assure you I wrote you at least one you did not get, as I found it today in a clean envelope among my things just arrived from Hilton Head,—a long letter that I wrote out in the open air one night at Hilton Head, when I was officer of the guard & had to sit up. I will try to tell you something of our later expedition, which certainly merits the name from the rate at which we came back. Since we got back, we have been in a chronic state of change, having moved our encampments, first inside the entrenchments, then out again, then in again, and so on, according to the supposed movements of master Reb, and are now on picket or rather garrison duty in some rifle pits we have dug just outside of the town.

We were suddenly relieved from Provost duty to join the regiment, which was ordered to the front the next day. We left our official chairs in the old Post office in Jacksonville, whence we distributed justice to the trembling citizens of Jacksonville & all the secession rascals in the neighborhood who took the oath of allegiance—such were our instructions—and established markets and the prices of sweet potatoes and eggs by our imperial edict,—and occupied a whole block of brick stores—and didn’t get up at reveille. All this luxury we exchanged for the camp & and the knapsack girded on our armor and went marching along to subdue Florida and her rebel cattle, and exalt the name of our generals. On the 18th ult. we started and marched about seventeen miles.—I was put in charge of some fifty recruits and stayed with them until the fight. Just before we reached the end of our day’s march, we passed through a swamp which wet our feet throughly, and from that time until a day after we returned to Jacksonville, my feet remained soaked, night & day. The principle result of this day’s march consisted in Smith, Captain Walton’s boy, shooting himself through the neck with an old fowling piece which he had picked up, and concerning which I had given him a solemn warning not two hours before, without any effect, of course. He just missed the jugular vein, & consequently, instead of killing himself, is only laid up in the hospital for one or two months. We camped in a swamp, & started early next morning, beginning the march by wading through half a mile of water, in some places two feet deep. We reached Baldwin and were joined by the four companies of our regiment who had been set out beforehand; this day’s march brought us to Barbour’s, as the place is called, a beautiful place on the St. Mary’s where the cavalry had had some fighting before. Here we found all the troops encamped who had fallen back previously, mostly in wigwams, which looked very comfortable and picturesque. The next day the 20th was the eventful one for our expedition, we started in the morning without the smallest idea of being stopped, at least until we got to Lake City, twenty hours afterward we came limping back, tired to death, chestfallen and demoralized for the time being. We were roused soon after five, our regiment was in the rear of the whole column, and did not get off till near eight. My men were supplied with axes & shovels & acted as pioneers, we marched abreast of the1st N. Carolina, to guard against any surprises, one each side of the road, for in this country, it is as easy to march by the side of the road as in it. Before the end of the morning, I got very tired running backward & forward after my men, and when we were halted for half an hour after marching nine or ten miles, felt more used up than at the end of either of the previous two days, & did not like the idea of ten miles more, which Gen. Montgomery said we must accomplish, so as to enter Lake City fresh the next day. After marching a few miles more, we suddenly caught up with all the trains which had come to a halt in the road, doubtless at this time the fight was just beginning , and halted ourselves to rest. While we were resting, all of a sudden, we heard artillery ahead, some miles apparently, and the firing soon became very rapid. This must have been between two and three in the afternoon. What could be the matter? Surely the enemy could not be in force ahead. We thought they were probably posted in the woods & were harassing our advance & our batteries were shelling them out.

Presently dispatches came for the Colonel, and we were immediately ordered forward. My pioneers were sent to the rear and I joined Company B. It was evident we were in for a fight, and I at least did not suppose we should be fifteen minutes in dislodging the rebels and serving them as the cavalry had served the Militia Artillery, having conceived a great contempt for the Florida Militia from what I had seen of them at Jacksonville, where we had a number of prisoners.

From the time we were ordered forward, the way we were managed was unlucky, to say the least. We found a moment to cap the guns and then hurried forward at the double-quick. Before we reached the battlefield, there was not a knapsack left, the men threw away everything to lighten themselves and I finally followed their example, trusting that they would be collected & [unknown word] after, not because I felt the weight at all, for sore feet & shoulders were cured by the prospect of a fight, and I did not feel the slightest bit of fatigue till we had left the field & were ten miles on our way back. I thought however, it might be troublesome in the battle, and so away went blankets, shirts and new [unknown word], never to appear again, unless I find them in the possession of some captured rebel, when we make our next advance if such a time ever comes, which it certainly will not at present. As we approached the battlefield, the cannonading became positively terrific, and drowned all other noises. As I said, the men primed their pieces as we came to the scene of engagement, and in their excited state, the sternest warning and threats did not prevent a number of accidental discharges. I heard a musket go off behind me and a cry of pain, but I did not stop to look around. I found out after the fight that this was one of our men, one of the worst in the company, who had wounded himself & killed a man near him by the careless discharge of his piece. One of our sergeants wounded himself in the same way, and has since been reduced to the ranks in consequence. It is positively horrible to lose men in this way, & is more demoralizing to the men than the loss of ten times the number by the enemy. The men are not sufficiently familiar with the handling of their pieces when loaded, & the lack of discipline in this respect caused a great deal of trouble on the field, the men naturally fearing to go ahead at the risk of being shot by others in their rear. You can have no idea of the difficulty of making the men carry their pieces properly, and not according to their own notions. It would do a great deal of good to have one or two men shot for negligence in this respect—a severe remedy—but the only one that would be fully effectual.

After getting in line in the field for some time we were not exposed to a very severe fire, most of the enemy’s shells were too high & cut the trees to pieces above us.

George Morris, the only man that we know of killed outright in the company, was struck down by the left of a tree after being wounded by a bullet. We lost most of our men in the retreat. After standing some time, firing away at the enemy whom we could just see between the trees, the colors advanced and the whole line followed with a cheer. At this the rebels opposite were seen to break and run. I was much too taken up with what was taking place about me to notice much of anything else, and did not see what other soldiers did, that our artillery had retreated in confusion, leaving several pieces and that the rebals were flanking our right. This caused the regiments on our right to give way, after having suffered very severely, much more so than we, who were not in the hottest part of the field. The 1st North Carolina of our brigade retreated in great confusion, and we were left the last regiment in the field, and in great danger of being cut off, which the rebels might have done, if they had understood their advantage. The sudden retreat of the whole line was however, completely astounding to me, not understanding the circumstances, as I was just congratulating myself that we were going on so well, and expecting an order for a charge presently.

Now it was that the trying [unknown word] came; the rebels, seeing us run, rushed forward with cheers and poured in a more accurate fire than they had done before. I got a considerable distance behind the regiment as they retreated, and looking toward the right saw that the rebels were coming along with very unpleasant rapidity, and the bullets began to sing round my ears in such a way as to excite a disagreeable suspicion that they had caught sight of my sword. I had no shoulder straps, which I had not worn for a month, as they were on my dress coat I left at Hilton Head. There were a number of stragglers on my right and left, who had rushed forward & been fighting on their own account, several of these were hit, and I shall never forget the cry of agony of one poor fellow who was hurrying to catch up to the rest & fell forward on his hands & knees disabled, for the men expected no mercy if taken remembering Fort Wagner, & made desperate exertions to get away. We passed though water knee deep both advancing& retreating & many stopped at all hazards to drink the muddy water. It is very satisfactory to hear that our wounded are suppose to have been treated well. [Editor’s Note: Actually, many of the colored troops were murdered on the field by the Confederates.]

After retreating some distance, we got out of fire, & reformed the line & Col. [?] made the men go through the manual to steady their nerves. After the retreat began, Captain Walton & myself were separated & saw nothing of each other till we all arrived at Barbour’s again, he with one detachment of the company and I with another. As generally happens, [unknown word] men got very much mixed up and a number of the 1st North Ca. were also among them. After retreating from the field we halted collected the scattered men & rearranged the companies.

Not to particularize, we marched out eighteen miles back again & arrived at Barbour’s at two o’clock the next morning, you may imagine in what condition.

Instead of any rest as we expected we were obliged to march the next morning, & trudged on all day over the same road we had [unknown word], and halted near Baldwin. We were ordered to reach Jacksonville that night. This would have been impossible, as least for most of the regiment, it would have been a march of over seventy miles in two days, in addition to the battle.

On the 22nd we reached Jacksonville, after the hardest day of all. After getting near Camp Finnegan, eight miles from Jacksonville, we were obliged to return several miles, & and tow down a train on the railroad, containing some of the wounded & some provisions, which were absolutely necessary as the men were half starved. At Camp Finnegan we pitched into a lot of commissary stores, which they were glad enough to get eaten up, as they expected to destroy them.

For two or three days after getting here, the men had hardly anything to eat, as it was nearly impossible to get rations. We have been peculiarly unfortunate, having lost all our hard tack by the wreck of the Burnside (?), as well as our clothes on the march & partly to the horrible bread which is baked for the men.

I have written a letter long enough for a Herald correspondent. You need not read it unless you like, but I get excited myself in writing & like to tell you all about it, and moreover it is the regular thing for new recruits to [unknown worn] on their first experience of actual service. I like to tell you about everything, as I should if we were talking together.

I am very much interested in Sherman’s movements. I have not cared much for the papers hitherto, but have more time now, & will read all you send me. I like to know what you think of affairs in general, as you can judge where you are better than we can.

Faithfully, your brother Robert

John S. Moore, Robert Newell’s great nephew, says that Captain Newell:

“…was stationed during most of 1864 outside Charleston and entered the city the day after the evacuation in February 1865. His letter about entering Charleston with his troopers and the condition of the shelled out city is most vivid. He remained in the Charleston area till the regiment was mustered out in August. His letters from this period should be of great interest to Charleston historians.

“His letters should be of particular interest to those studing the role of Black troops in the war. His continuing problem was that his troopers were not being paid according to the terms of their enlistment, causing moral problems. Finally Congress passed a bill authorizing equal and full pay to those colored troops who were free men as of April 1961. Not all the troops qualified, but his colonel, a Quaker, did not believe in slavery and could therefore have all the troops swear that they were free men. Newell describes this event, known as ‘the quaker oath.’ Rather an historic moment.”

Robert Newell’s Obituary from the Albany Law Journal, 1883:

We regret to be compelled to chronicle the death of Mr. Robert R. Newell, the editor of the Index-Reporter. He died at Cambridge, Mass. On the 23rd ult., after a few days’ illness, of pneumonia, at the age of thirty-nine. He was in the class of 1865 at Harvard, but left college to enter the military service in the civil war, in December, 1863. He became a captain in the 54th Massachusetts regiment and served until the end of the war. He afterward received his degree at Harvard, was two years at Harvard Law School, and subsequently practiced at the Boston bar. He was never married. Mr. Newell was a singularly modest and conscientious man. His editorial labor was characterized by rare discrimination and intelligence, and unfailing industry and fidelity. Our readers will regret with us that he should have been called away so soon from a life so full of faithful performance and fair promise.

Letter to the Christian Recorder

April 2, 1864

THE CHRISTIAN RECORDER

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

MR. EDITOR: – Sir: – It is with pleasure that I now seat myself to inform you concerning our last battle: thus we were in Co. B, on the 20th of Feb. Mr. Editor, I am not sitting down to inform about this battle without knowing something about it.

The battle took place in a grove called Olustee, with the different regiments as follows: First was the 8th U.S.; they were cut up badly, and they were the first colored regiment in the battle. The next were the 54th Mass., which I belong to; the next were the 1st N.C. In they went and fired a few rounds, but they soon danced out, things were too warm for them. The firing was very warm, and it continued for about three hours and a half. The 54th was the last off the field. When the 1st N.C. found out it was so warm they soon left, and then there was none left to cover the retreat. But captain J. Walton, of the 54th, of our company, with shouts and cheers, cried, “Give it to them my brave boys! Give it to them!” As I turned around, I observed Col. E.N. Holowell standing with a smile upon his countenance, as though the boys were playing a small game of ball.

There was none left but the above named, and Lieut. Col. Hooper, and also Col. Montgomery; those were the only field officers that were left with us. If we had been like those regiments that were ahead, I think not only in my own mind, but in the minds of the field officers, such as Col. Hooper and Col. Montgomery, that we would have suffered much loss, is plain to be seen, for the enemy had taken some three of four of their pieces.

When we got there we rushed in double-quick, with a command from the General, “Right into line.” We commenced with a severe firing, and the enemy soon gave way for some two hundred yards. Our forces were light, and we were compelled to fall back with much dissatisfaction.

Now it seems strange to me that we do not receive the same pay and rations as the white soldiers. Do we not fill the same ranks? Do we not cover the same space of ground? Do we not take up the same length of ground in the grave-yard that others do? The ball does not miss the black man and strike the white, nor the white and strike the black. But, sir, at that time there is no distinction made, they strike one as much as another. The black men have to go through the same hurling of musketry, and the same belching of cannonading as white soldiers do.

It has been nearly a year since we have received any pay; but the white soldiers get their pay every two months; ($13.00 per month,) but when it comes to the poor negro he gets none. The 54th left Boston on the 28th of May, 1863. In time of enlisting members for the regiment, they were promised the same pay, and the same rations as other soldiers. Since that time the government must have charged them more for clothing than any other regiment; for those who died in a month or two after their enlistment, it was actually said that they were in debt to the government. Those who bled and died on James’ Island and Wagner, are the same. Why is it not so with other soldiers? Because our faces are black. We are put beneath the very lowest rioters of New York. We have never brought any disgrace by cowardice, on the State we left.

E.D.W.

Co. B, 54th Mass., Vol.

Jacksonville, Fla., March 13th, 1864.

This is ITEM #60542 from the Accessible Archives, Inc. Database and Web site at http://www.accessible.com/. You or your organization must be a licensed subscriber to access the databases on its site. This letter is posted here with the kind permission of Mr. John Nagy, Accessible Archives, Inc.

Letter to the Christian Recorder

September 24, 1864

THE CHRISTIAN RECORDER,

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

FOLLY ISLAND CORRESPONDENCE.

Folly Island, S.C., Aug. 21st, 1864.

DEAR RECORDER: – I sit down this beautiful morning to let the many admirers of your useful paper have some idea of things in this department. The sun arose arrayed in all the beauties of the brightest ethereal. We were mustered this morning, according to custom, for pay, and our Colonel administered the oath presented by the recent law concerning persons of African descent, in the military service of the United States’ and touching the law of 1861 concerning free, able-bodied citizens from that time forward. The reason given for administering this oath is in order to procure the just wages of a soldier. It looks like going a step backward to be obliged to swear that we are free in order to get our just dues, having been born in states where our right to freedom was not questioned. But we had no right to doubt the veracity of our gallant Colonel, and we consented in our company to a man; and we now have our names enrolled with the promise of our just pay, for once in seventeen months: that is better than never!

If we should not be again deceived, our distressed wives and children will hail the happy moment to be relieved from suffering, and they may with glad hearts offer up prayers and tears for the speedy end of this great rebellion, and the enjoyment of our firesides in peace and happiness. In the promise of our pay, we were not promised promotion. I will say something about the prejudice in our own regiment when we returned from Olustee to Jacksonville. One of our Captains was sick, and there was no doctor there excepting our hospital steward, who administered medicines and effected a cure; he was a colored man, Dr. Becker, and a competent physician, and, through the exertions of this recovered Captain, there was a petition got up for his promotion. All the officers signed the petition but three, Captain Briggs, and two lieutenants; they admitted he was a smart man and understood medicine, but he was a negro, and they did not want a negro Doctor, neither did they want negro officers. The Colonel, seeing so much prejudice among his officers, destroyed the document, therefore the negro is not yet acknowledged.

Notwithstanding all these grievances we prefer the Union rather than the Rebel government, and will sustain the Union if the United States will give us other rights. We will calmly submit to white officers, though some of them are not so well acquainted with military matters as our orderly sergeants, and some of the officers have gone so far as to say that a negro stank under their noses. This is not very pleasant, but we must give the officers in company B, of the 54th Massachusetts regiment, their just dues; they generally show us the respect due to soldiers, and scorn any attempt to treat us otherwise.

Since we have moved into Fort Green, our officers have advised us to improve in the drilling of heavy artillery, and show the advantages derived therefrom. They give us all the encouragement they can to best up under the grievance of not getting our pay; telling us that firmness of purpose and rigorous performance of our duty must command respect, and our good example may be a lasting name in history, which must have a tendency to elevate our race; there is no great end accomplished without long perseverance and many sacrifices of comfort; but, suffice it to say, enough has been said in regard to elevation, promotion, &c.

Let us look a little to the majority of our race. Do they use every means to elevate themselves? Do they sacrifice carnal enjoyments to procure wealth, in order to engage in respectable business, to concentrate their capital and associate in companies to give employment to the accomplished colored book-keeper or salesman, and command respect from other nations? All this has a tendency to elevate our race, and the more wealth we possess the more we shall be respected in commercial society. All this must be accomplished before we can fully realize equality; let each patronize the other in business, and give aid and good counsel, and use our influence to start young men in business. When these things are practised, among us then we will command the respect of the Anglo-Saxon race.

I must tell you something about our living in the army. We have not had enough to eat for several weeks, being on three quarter rations, and for the last twelve or thirteen days, have been cut short of that, having no beans, peas, rice or molasses; in a word, nothing but salt beef and pork, tea and coffee half sweetened, and one loaf of bread per day or three-quarter rations of hard tack or bread. We would think it impossible to live on at home, but here we are obliged to; and, beside the short allowance of the government, it is said we are cut shorter by the quarter-master’s department. From all appearances, our molasses has been out in the rain; our coffee has the essence extracted before it comes to camp, and then the sugar is very sparingly used. This may be a saving to the United States, but it is a grievous nuisance to us.

Concerning things before Charleston, the rebels still throw an occasional shell into our camp on Morris Island, which is quite annoying, but no recent casualties. The Union men vigorously return the fire, shelling the rebel camp, hospital, and every available place to do the most damage in retaliation for their inhuman and unjust fighting tactics.

Yours truly,

FORT GREEN.

This is ITEM #61803 from the Accessible Archives, Inc. Database and Web site at http://www.accessible.com/. You or your organization must be a licensed subscriber to access the databases on its site. This letter is posted here with the kind permission of Mr. John Nagy, Accessible Archives, Inc.

Two letters from Coroporal James Henry Goodiing

James Henry Gooding was born into slavery on August 28, 1838 in North Carolina. At a very young age his freedom was purchased by a James M. Gooding, who may have been his father, and he was sent to New York City.

The 54th Massachusetts was sent to the barrier islands of coastal Georgia and South Carolina. Providing a description of the South to the Mercury, Gooding remarked in June 1863 that all he saw was “…stink weed, sand, rattlesnakes, and alligators. To tell the honest truth, our boys out on picket look sharper for snakes than they do for rebels.” This monotony would not last long. Less than a month later, Gooding participated in the storming of Fort Wagner near Charleston, SC, depicted in the 1989 film Glory. Describing the action at Fort Wagner to the Mercury, Gooding said, “We met the foe on the parapet of Wagner with the bayonet…”